First, it was cottagecore, filling our feeds with sourdough starters and rustic linen. Then came the sharp, symmetrical pastels of the Wes Anderson trend, followed by a tidal wave of Barbie pink that painted the internet for a summer. Each aesthetic arrived like a weather front, dominating the landscape completely for a short time before vanishing just as quickly, leaving behind only a faint digital echo. They were cultural costumes, tried on for a season and then relegated to the back of the closet.

Into this cycle stepped Studio Ghibli, its decades of patient, handcrafted animation compressed into a one-click selfie generator. The resulting “Ghibli-fication” of our profiles was not a deep engagement with Hayao Miyazaki’s themes of environmentalism and pacifism; it was simply the next costume off the rack. The speed with which we adopted and then abandoned it reveals a difficult truth. Our treatment of Ghibli was a symptom of a much larger cultural pattern, one where even the most profound art is rendered disposable by the internet’s insatiable appetite for the new.

When everything becomes an aesthetic, nothing remains itself

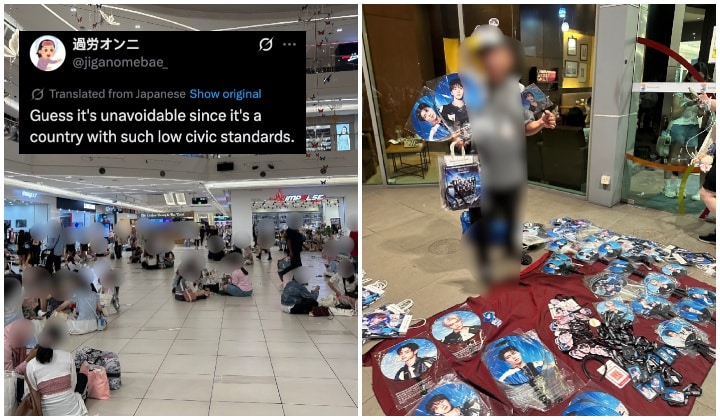

Platforms thrive on legibility. Content needs to be instantly recognizable, easily categorized, and simple enough to reproduce at scale. This creates enormous pressure to reduce complex cultural artifacts into their most surface-level visual markers. A Wes Anderson film becomes “symmetrical shots in pastel.” A hit song from Raye (that marked her leaving a music label and following creative freedom) becomes just a fleeting 20-second TikTok dance about rings on fingers and finding husbands. Ghibli’s intricate storytelling about war, labor, and the natural world gets flattened into “soft colors and big eyes.”

Learn more here.